DO ISO CERTIFICATES ENHANCE INTERNATIONALIZATION? EXAMPLE OF PORTUGUESE INDUSTRIAL SMEs (PART 1)

This article is a free translation of the work of Luis Pacheco, Carl Lobo, and Isabel Maldonado.

Introduction

The debate on factors affecting the international development of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) continues to generate interest in the literature. Traditionally, the literature has widely emphasized the obstacles or barriers to internationalization and the main factors that enhance the international performance of SMEs.

Given the limitations of the domestic market, internationalization can provide potential profits for an individual firm for two main reasons:

(1) internationalization offers new opportunities to create value by providing access to new resources, knowledge, business practices, and foreign stakeholders;

(2) internationalization helps to reduce income fluctuations by diversifying risks in several countries.

Nevertheless, the asymmetric nature of the information present between domestic firms and foreign customers presents a significant barrier to the international development of SMEs. This paper is a contribution to the literature on the role of internal capabilities and skills of SMEs in determining their export activities, testifying to the impact of firm certification, namely in terms of firm quality, environmental, health and safety management systems, on reducing information asymmetry and improving export performance.

Using unbalanced panel data on 1,684 Portuguese industrial SMEs from 2010 to 2020, and using other determinants of internationalization as control variables, we investigate the relationship between certification and internationalization. This paper fills a gap in the literature because (1) it distinguishes between the impact of different types of certifications **(ISO 9001, ISO 14001, and ISO 45001)** on different export markets, and (2) it explores the possible moderating role of some variables in the certification-internationalization relationship. To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to examine the impact of firm certification on internationalization. The results suggest the importance for firms, especially in low- or medium-low-tech sectors.

The Impact of Certification on the Internationalization of the Firm

The adoption of various types of certifications by firms has grown considerably over the past decades. Such certifications can be seen as playing a dual role: a tool for internal management, and a way to communicate a firm’s qualities to stakeholders. In this article we focus our attention on this second role.

In an increasingly complex and global environment, SMEs face many challenges in international trade, finding it difficult to go out and explore the potential opportunities offered by different markets. Incomplete information presents a significant barrier to export expansion, either in terms of extensive margins (exporting new goods or entering new markets) or intensive margins (increasing exports to current trading partners). Given the serious information problems associated with export activities, adding new countries of destination or new goods and services can be challenging, especially for SMEs with limited international experience and a lack of human resources. As some authors argue, incomplete information creates friction in the matching process between buyers and sellers across national borders; hence, it is an obstacle to the development of export activities. These problems are even more serious for SMEs located in peripheral countries, such as Portugal, and producing differentiated products.

Internationally recognized certification seals issued by third-party organizations can be seen as a way to address market failures and help firms overcome the responsibility of foreignness. Founded in 1987, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 9001, which defines standards for certifying products, structures and administrative systems, has become the world’s leading quality assurance system, with more than a million companies and organizations in more than 170 countries certified to ISO 9001. For example, at the end of 2020, there were 6,147 Portuguese firms certified to ISO 9001, up from about 4,800 in 2010. Over the past couple of decades, ISO certifications have spread to other areas, and firms have increasingly sought to assemble a set of certifications to meet customer requirements and maintain their competitiveness in national and international markets. For example, ISO 14001 serves as a tool to promote environmental and sustainable management, and ISO 45001, which replaced OHSAS 18001, sets the requirements for a health and safety management system. These three standards are usually referred to together by the acronym QES (Quality, Environment, Safety). In addition, ISO 26001 confirms the company’s commitment to social responsibility and ISO 37001 serves as the standard for the anti-bribery management system.

The purpose of the international standard is to provide clear identifiable references, recognized worldwide, and thus indirectly stimulate international trade by signaling product quality, reliability as well as firm values and sound business management. Note that certification does not guarantee that a firm is better or more efficient than its competitors. Nevertheless, several studies suggest that certified firms outperform non-certified firms, and the reasons are mainly due to improved internal business processes and lower costs. However, the impact on financial performance is mixed. How certification strengthens a firm’s competitive position has been studied by some authors who take a resource-based view (RBV), which suggests that firms create competitive advantage by reconnecting resources and capabilities that are difficult for competitors to copy. From the RBV perspective, ISO certificates are resources that can act as “engines” of internationalization opportunities, reinforcing the protection of a firm’s competitive advantage. This argument assumes that certification is a self-regulatory tool that firms voluntarily adopt and co-develop to gain several internal benefits: compliance with organizational, environmental, legal and regulatory requirements, etc. However, there is reason to believe that the competing assumption that certification represents a coercive response to external incentives and industry pressures-for example, financial incentives to obtain certification or having some form of mandatory certification to access a regulated market. This argument can also be explored according to institutional theory, which analyzes the social and cultural pressures forcing firms to become more isomorphic. The institutionalization achieved by some types of certification has made them a necessary requirement for market entry. Thus, certification is a response to stakeholder pressure rather than something voluntarily adopted to improve a firm’s overall performance and use of resources and capabilities. In addition, certification also contributes to the problem of information asymmetry by signaling to the market the quality of the firm. According to most studies, external motives of SMEs seem to be more predominant than internal reasons, as certification allows firms to cope with external pressures and signal their position in the global marketplace. This is even more important in an international context, since there are limited opportunities to verify and evaluate a large number of potential suppliers.

The literature examining the relationship between certification and internationalization is recent and limited to a set of descriptive or specific papers on the effects on trade resulting from the adoption of QES standards by firms, mostly large ones. With respect to environmental certification, evidence suggests that export considerations and government requirements were important drivers of certification, as well as the desire to reduce costs and improve product quality. Using a large sample of Canadian manufacturing SMEs, evidence suggests that adoption of ISO 9001 was associated with an increased likelihood of exports and a higher ratio of exports to sales. A survey of firms located in six major trading partners in Israel showed that while price and quality are still considered the most important factors in international sourcing, environmental certification is often taken into account. The authors showed that the adoption of SA 8000 certification implies an increase in bilateral exports of goods and services, especially in developing countries. Using data collected through a questionnaire to which 231 Spanish agri-food companies responded, showed that ISO certifications have a positive effect on the level of internationalization of companies, thus confirming the RBV theory. Recently evaluated the relationship of quality, environmental and safety standards in international trade in developed and developing countries. Their results showed that the adoption of these standards, especially ISO 9001, had a positive and significant impact on exports of goods and services in developing countries. A similar result was found in a recent review, which showed that organizations recognized that the domestic effects of adopting ISO 14001 were positive, in the form of increased profits and exports.

Because of potential endogeneity issues, it is difficult to study the export impact of adopting QES standards. The increase in exports may be a consequence of earlier adoption of the standards, but it may also be a trigger for the adoption of such standards. We will keep this possibility in mind in our study.

Following the literature presented above, and from the firm’s RBV perspective, it is assumed that firm certification is positively related to internationalization. However, this effect may vary across certification types, export destinations, and industry sectors. For example, the relationship between certification and internationalization can be expected to be stronger for firms whose exports are focused on the European Union (EU) market, rather than for firms exporting mainly to the rest of the world. Naturally, requirements for exporting to markets outside the EU differ between countries, but for simplicity and because of the database to be used, we assume that EU countries are more demanding and adopt stricter rules; hence, stakeholders and institutional pressure to obtain certain certifications are stronger. In addition, ISO certificates can be expected to be more relevant in sectors such as food and beverage or pharmaceuticals, while they may be less relevant in less competitive and less regulated sectors.

Differences in levels of internationalization among firms can be related to differences in firm-specific strengths as well as differences in the characteristics of the industry in which firms operate. Industry classification is an important factor affecting internationalization because industries represent different financial structures, levels of competitiveness, and resource needs. In the context of the relationship between certification and internationalization, it is relevant to examine whether there are significant differences between certified and non-certified firms in certain industries, classified according to their technological intensity.

As a result of this literature review, we can now formulate the first set of hypotheses to be tested:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The degree of firm internationalization is positively related to firm certification;

Hypothesis 1.1 (H1.1).

Firm internationalization is positively related to firm certification;

Hypothesis 1.2 (H1.2).

This effect differs depending on the type of certification (quality, environmental, and safety);

Hypothesis 1.3 (H1.3).

This effect differs depending on the export destination (EU and non-EU countries);

Hypothesis 1.4 (H1.4).

This effect differs between sectors (classified according to technological intensity).

Additional determinants of internationalization

Although our paper focuses on the relationship between firm certification and internationalization, it includes a set of control variables to exclude alternative determinants of the levels of internationalization of the sampled firms. In addition to their direct effect on internationalization, we intend to examine the moderating role of some organizational characteristics in influencing the certification-internationalization relationship. These variables are traditionally used in studies of the determinants of internationalization: firm profitability, age, size, and debt.

Regarding these control variables, we formulate the following set of hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The correlation between firm certification and internationalization differs between less and more profitable firms, with the latter exhibiting higher levels of internationalization;

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The relationship between firm certification and internationalization differs between younger and older firms, with the latter exhibiting higher levels of internationalization;

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The correlation between firm certification and internationalization differs between large and small firms, with the former exhibiting a higher level of internationalization;

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

The correlation between firm certification and internationalization differs between firms with more or less debt, the latter exhibiting a higher level of internationalization;

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

These variables play a moderating role in the relationship between firm certification and internationalization.

Materials and Methods

Dependent and independent variables

The dependent variable, exports, is measured as the ratio of total exports to total sales. This variable will also be considered to distinguish between exports to the European Union (EU) and exports to markets outside the EU. The reason for this broad distinction is the availability of data, as the database does not provide disaggregated data by country for firms’ exports. The independent variables associated with firm certification are calculated as dummy variables, with certified firms representing “1” and “0” otherwise. We consider three different types of certifications: ISO 9001, ISO 14001, and ISO 45001/18001.

Although our paper focuses on the relationship between firm certification and internationalization, we include the following set of control variables to exclude alternative determinants: profitability, age, size, and debt. Profitability is measured by the ratio between EBITDA and total assets. For reasons of excess, the variables age (WHOLE) and size (SIZ) are measured as the logarithm of the number of years since the firm was founded and the logarithm of total assets, respectively. A firm’s level of debt is measured as total debt (TD = Total Liabilities / Total Assets) and its subdivision into short-term and long-term debt (respectively, STD = Current Liabilities / Total Assets and LTD = Long-term Liabilities / Total Assets).

Data and Methodology.

This paper analyzes a sample of SMEs from industrial sectors (codes 10 to 32 from the European Classification of Economic Activities – NACE – Rev. 2) obtained from SABI ( Sistema de Analise de Balanços Ibéricos.), a financial database maintained by Bureau van Dijk. Certification data were obtained from IPAC (Portuguese Certification Institute). Deviating from the list of more than 6,000 firms certified to ISO in 2020, applying the criteria for defining SMEs (Commission Recommendation 2003/361/EC) and thus excluding microfirms, considering only firms already existing in 2014 and representing at least six years of data for the period from 2010 to 2020, unbalanced panel data of 1,684 SMEs distributed in all industry sectors were obtained. The three most represented sectors are sectors 25 (Metal Products), 22 (Rubber and Plastic Products) and 28 (Machinery and Equipment) with 403, 163 and 136 firms respectively, while sectors 12 (Tobacco Products) are 19. (oil refining), and 21 (pharmaceutical products),

The sample consists of SMEs with an average age of 30 years with total sales of just over €11,000 million (of which €4,600 million are exports), total assets of €13,000 million, and an average EBITDA to total assets ratio of 9.22% in 2020. In 2020. 1,634 firms had ISO 9001 certification (up from 649 in 2010), 331 had ISO 14001 certification (84 in 2010) and 139 had ISO 45001/18001 certification (the first 22 in 2013). In addition to sector 10 (food), certified firms are more represented in capital-intensive sectors such as sectors 22 (rubber and plastic products), 23 (other nonmetallic mineral products), 25 (metal products), and 28 (machinery and equipment).

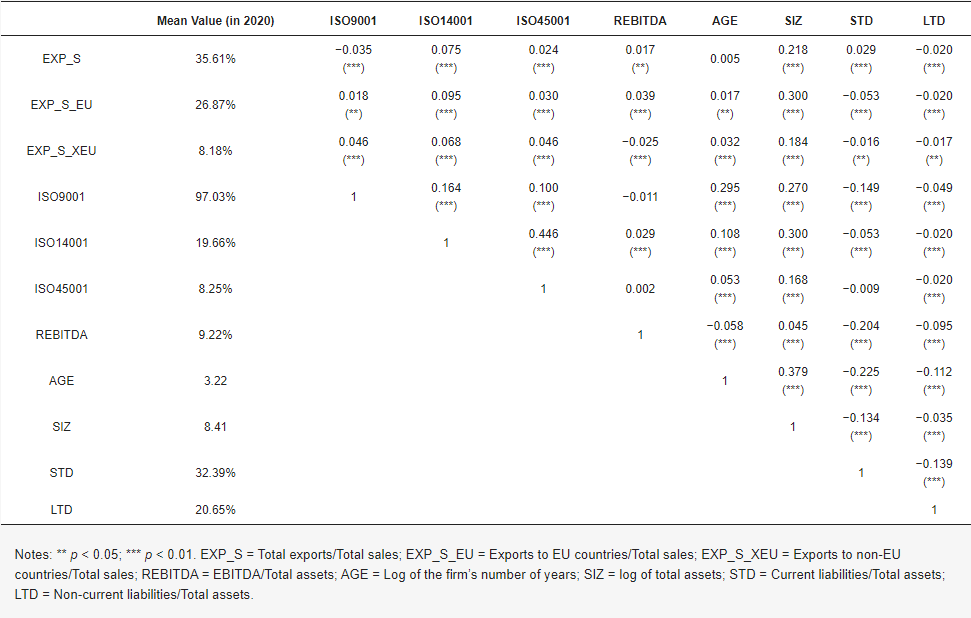

Before estimating the different models, we present in Table 1 the average values of the variables in 2020 and a correlation matrix. As for the correlation coefficients, they are generally low, indicating that there are no multicollinearity problems.

Table 1. Mean values and correlation matrix between independent variables.

To achieve the goal of our study, we apply panel data methodology, which can be evaluated using three different regression models: pooled ordinary least squares (POLS), fixed effects model (FEM) and random effects model (REM). Applying the Breusch-Pagan and Hausman tests to choose the most appropriate regression method, the results show that REM is preferable. Alternatively, we use three possible dependent variables (EXP_S, EXP_S_EU, and EXP_S_XEU) for the ISO certification and control variables of profitability (REBITDA), AGE, SIZ, and debt.

In addition, because the three different dependent variables are left-censored (obviously EXP_S, EXP_S_EU, and EXP_S_XEU variables have values between zero and one), we use the Tobit methodology. Tobit regressions are nonlinear; hence, the coefficients should be interpreted with caution and do not measure the real causal effect on the dependent variable. This effect is correctly measured only by the marginal effect; however, the coefficients retain the significance and sign of the marginal effects, which allows us to test our hypothesis.

The explanatory power of the REM model is determined by the overall R2, and the significance of the Tobit regression is estimated with respect to the Wald statistic χ2 . Note that running regressions with certification variables with a lag of one year, considering total debt instead of dividing it into short-term and long-term debt, using other measures of profitability (e.g., return on assets or return on sales), or excluding 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic did not produce different results.